The

Suntory

Family

A story of

pioneers

How the Founding House of Japanese whisky defied the odds, battled failure, and ultimately succeeded through a vision for bringing brilliance and joy to all

THIS STORY WAS PRODUCED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH GODFREY DADICH PARTNERS, A STORYTELLING FIRM CO-FOUNDED BY SCOTT DADICH, FORMER EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF WIRED. IT WAS EDITED BY ROBERT CAPPS, GDP’S PRESIDENT OF EDITORIAL AND FORMER EDITORIAL DIRECTOR OF WIRED.

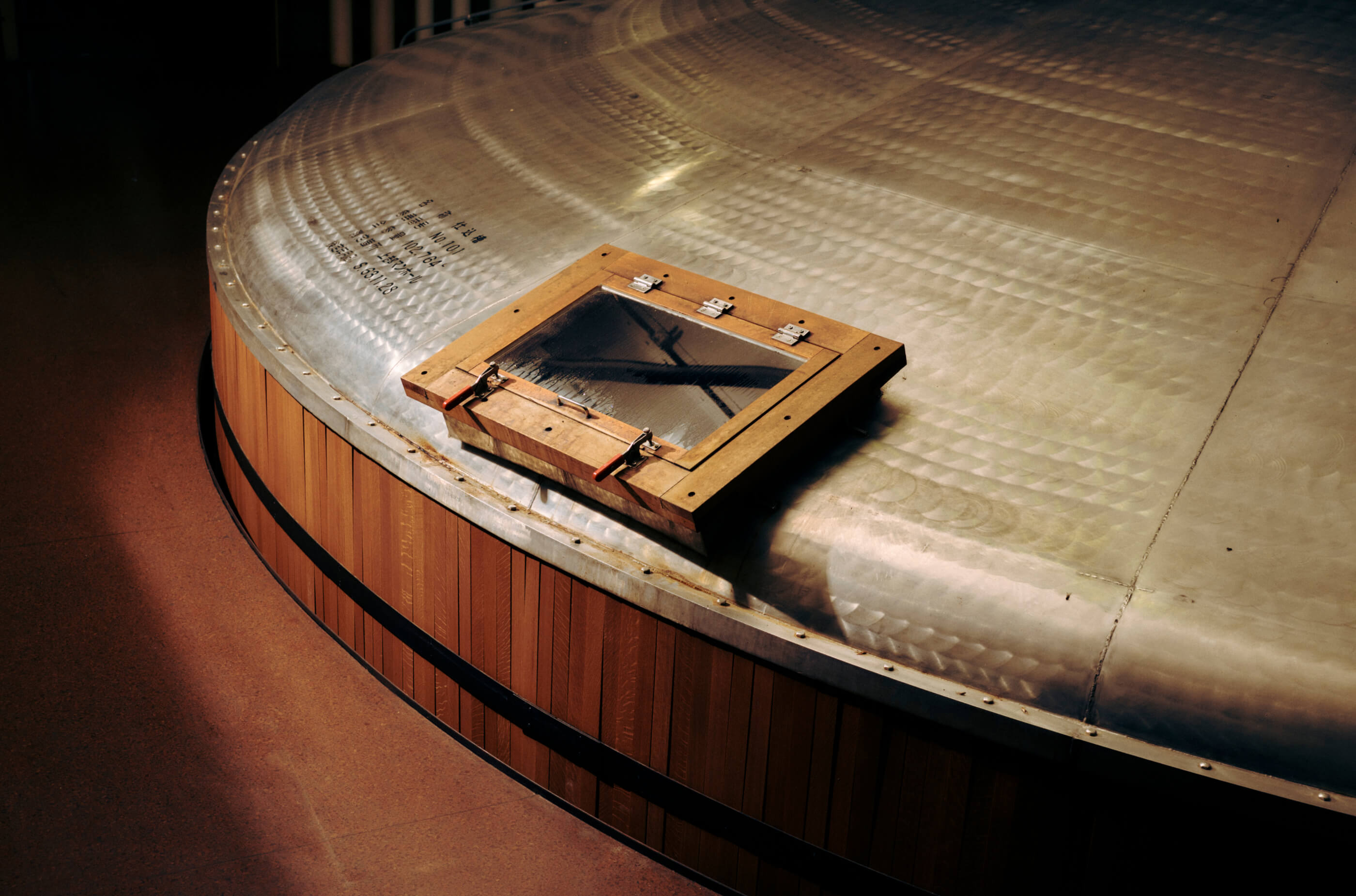

FROM PAST PHOTO ARCHIVES

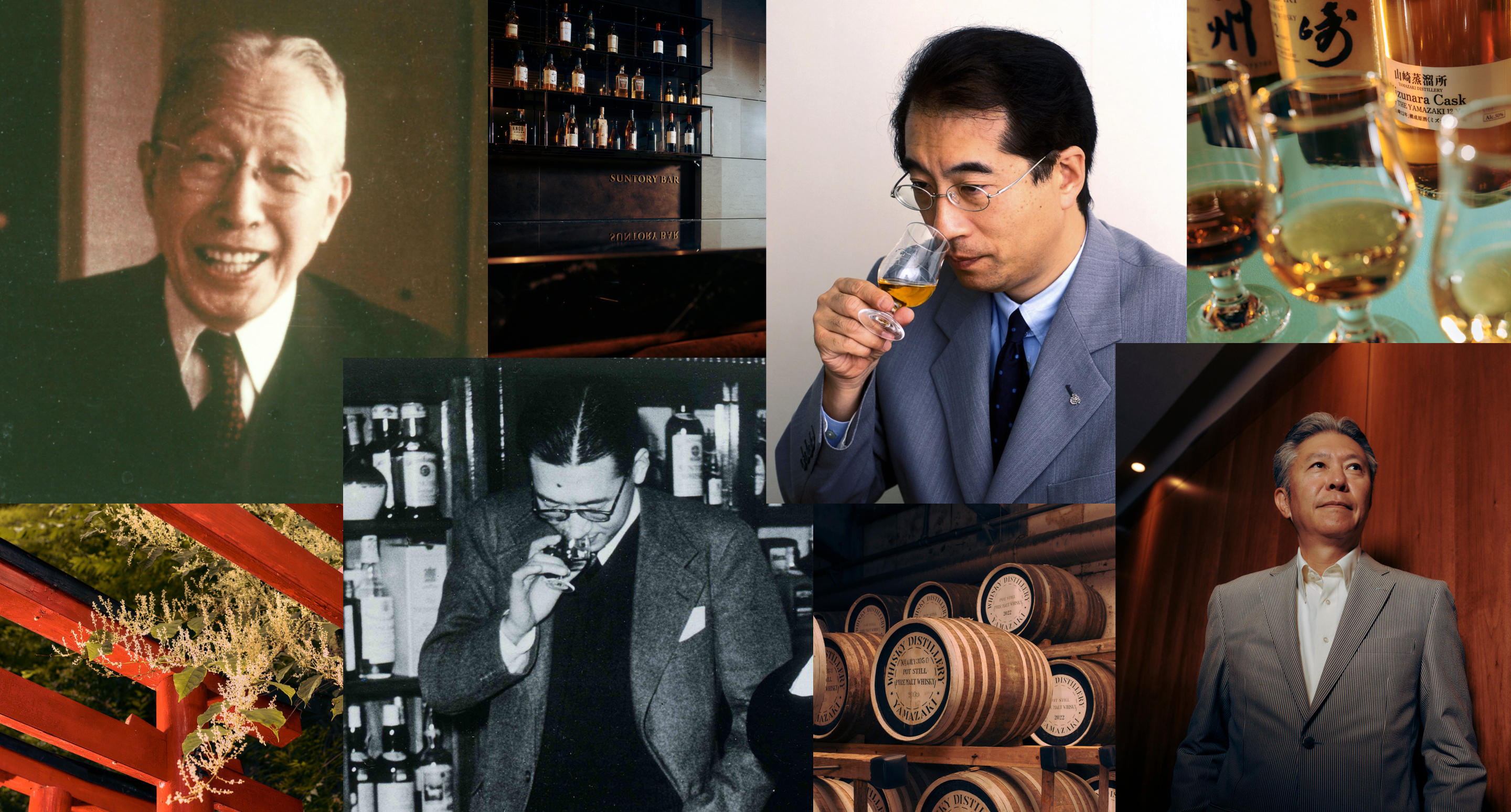

At the misty foot of Mount Tennōzan, where the pure and crisp waters percolating from the aquifers have stirred the souls of poets for millennia, Japan’s first (and its most famous) malt whisky distillery rises from a lush hillside of maple and bamboo. To enter Suntory’s Yamazaki Distillery at the southwestern fringe of Kyoto is to venture uphill, deeper into the forest, and into the dream that brought Shinjiro Torii to this spot almost a century ago. As the founding father of Japanese whisky, Shinjiro broke ground on Yamazaki in 1923 in the hopes of introducing the true taste of whisky to Japanese people. At the time, the West accounted for less than 1 percent of the Japanese liquor market.

“I’m taking up the challenge of making whisky,” he insisted, “because no one else is even trying.”

“I’M TAKING UP THE CHALLENGE OF MAKING WHISKY, BECAUSE NO ONE ELSE IS EVEN TRYING.”SHINJIRO TORII

Few visionaries are ever realistic, of course; they achieve greatness by seeing what others can’t, even if that means risking failure or being branded a fool. Shinjiro clung stubbornly to his belief that he could create a market for “Western liquors made by Japanese hands” if he focused on the enjoyment that awaited a new generation of Japanese whisky drinkers. In his view, and in that of the Torii heirs who honor his legacy at Suntory today, whisky was neither a vehicle for producing wealth nor promoting intoxication but for inspiring harmony—an elixir that would bring people closer together and kindle happiness in their hearts.

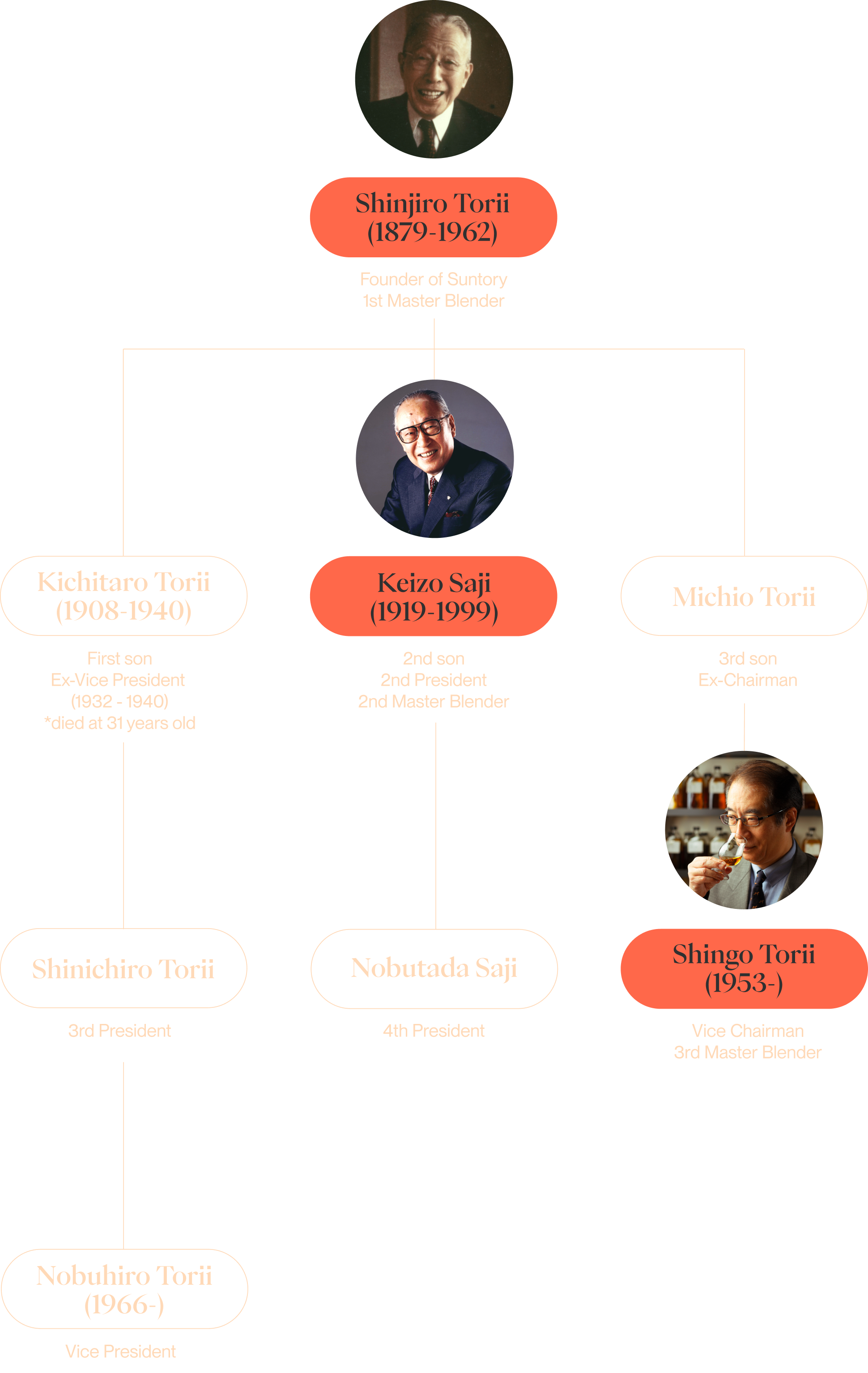

“Ever since I was a child, I was brought up with the notion that our business is always related to the happiness of people,” says Nobuhiro (Nobu) Torii, Shinjiro’s great-grandson and Suntory’s executive vice president and COO. Nobu oversees the company’s global footprint, which now spans beer, wine, nonalcoholic beverages, wellness products, and cultural and social contribution activities. When asked what differentiates Suntory from its competition, he answers, “Being a family-owned business makes a true difference. We have a different sense of time. What distinguishes Suntory is that we are a family of Master Blenders. It takes a hundred years to make a difference.”

“TRUE SUCCESS REQUIRES FAILURES. IT’S WHEN YOU FAIL THAT YOU REALLY LEARN SOMETHING.”NOBUHIRO TORII

From traditional single malts like Yamazaki and Hakushu, to the more approachable Toki, to the original Japanese blended whisky Kakubin and the luxurious Hibiki of Lost in Translation fame, Suntory is globally renowned for crafting subtle, refined, and complex expressions cherished by connoisseurs the world over. It’s difficult to imagine that barely 100 years ago there was no such thing as Japanese whisky. Or that Shinjiro had to fail multiple times before he managed to will Suntory Whisky into existence.

“It’s not easy being successful,” Nobu says, “because true success requires failures. It’s when you fail that you really learn something.” For 100 years, from 1923 to 2023, Suntory’s journey of pioneering Japanese whisky has been one of trial and error. This is a story about how one family, from the founder Shinjiro to his successors Keizo Saji and Shingo Torii, challenged the status quo—and pushed the boundaries of what whisky could be.

Torii

“HE REFUSED TO ACCEPT THE WIDELY HELD BELIEF THAT WHISKY COULD BE MADE ONLY IN SCOTLAND.”

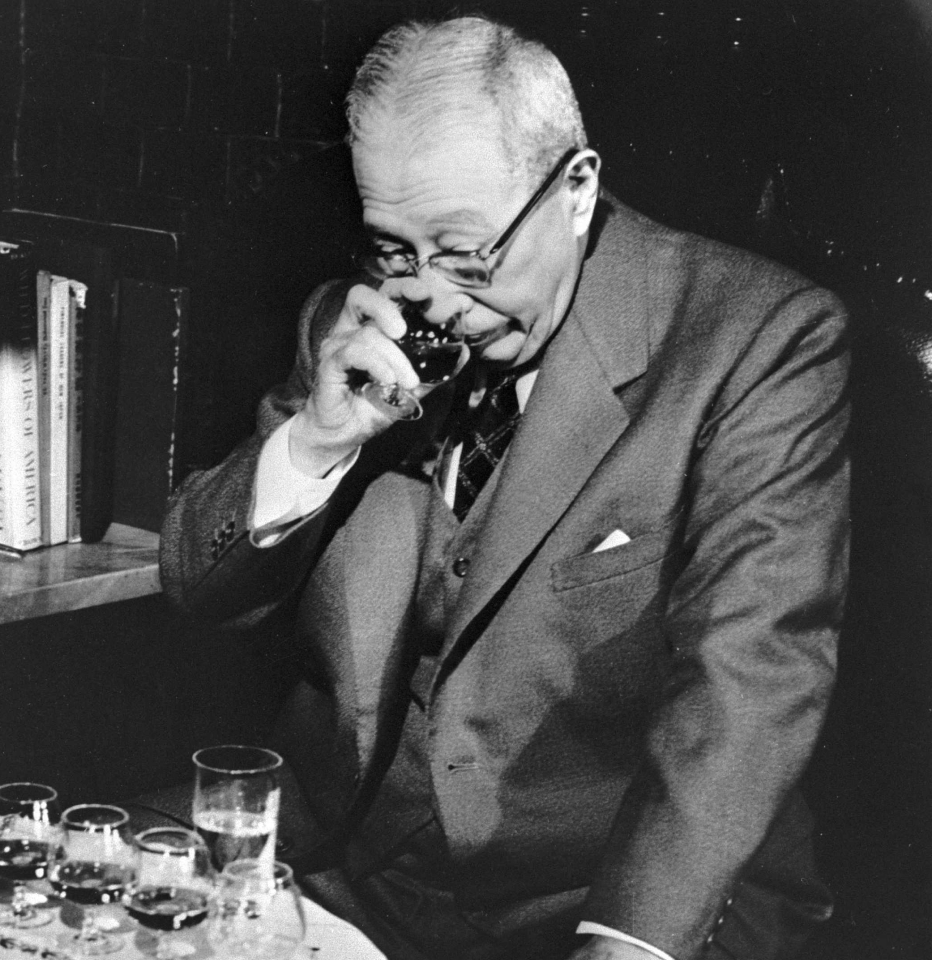

When Shinjiro Torii opened his small import store in Osaka in 1899, he had only optimism to sell. Just 20 years old and virtually penniless, Shinjiro hungered to accelerate the quest for the “civilization and enlightenment” that defined Japan’s ambitions during the turn-of-the-century Meiji period. Shinjiro stocked his shelves with European wine, but the bottles collected dust: the Japanese public was not accustomed to the delicacies of foreign spirits. This hard lesson cost Shinjiro his savings, but it also motivated him to create his first original blend, fit for the palate of Japanese people.

Desperate to salvage his inventory, he called on past experience. As a teenager, Shinjiro apprenticed at Konishi Gisuke Shoten, Osaka’s premier pharmacy that also imported quality Western liquors. There, he became fascinated with blending, spending most of his time mastering techniques and developing both his nose and palate. In 1907, Shinjiro introduced a sweet fortified port wine he named Akadama. The name referred to the red sphere of the sun, the source of all life, and previewed the philosophical foundation that later gave rise to Suntory’s name itself, a portmanteau of Sun and Torii. Akadama became a massive success; more than a century later, it’s still a beloved product. “My great-grandfather was good at creating taste,” Nobu says. “Blending was his gift.” Shinjiro was soon nicknamed “the nose of Osaka.”

Even with the success of Akadama, Shinjiro pined for an exotic liquor made entirely in Japan. He refused to accept the widely held belief that whisky could be made only in Scotland. Ignoring the advice of his own business associates, he wagered the company’s capital on a new distillery. “If we don’t just give it a try,” he said at the time, “we will not know whether our business is ever going to make it big or not.” This marked the genesis of Suntory’s “challenging spirit,” or pursuing new endeavors without fearing failure.

HIS DEVOTION TO MONOZUKURI IMBUED THE COMPANY WITH ITS RENOWNED COMMITMENT TO ARTISANAL SKILL.

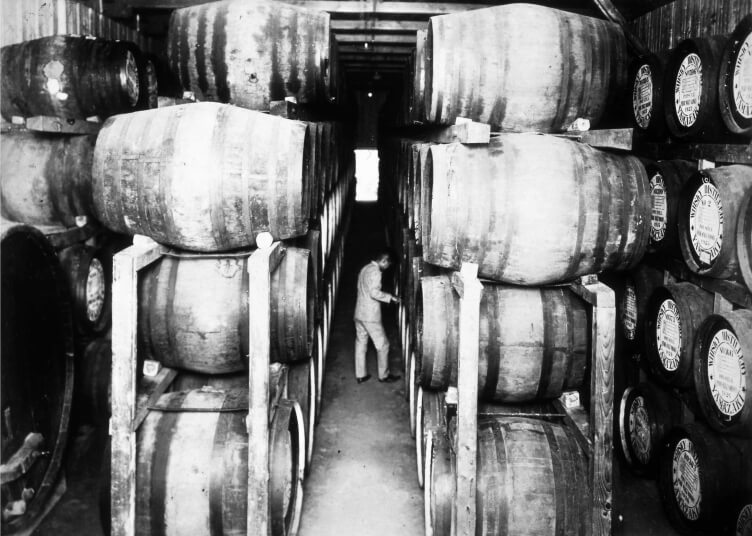

For his new “soul place,” Shinjiro staked out a humid slope at the confluence of the Uji, Kizu, and Katsura rivers, where the semi-soft water was deemed perfect for making whisky and the climate ideal for aging it. A nearby ancient Shinto shrine, with a spring-fed well and spigot, confirmed the site’s divinity; its water is still used by locals today. Because Yamazaki was Japan’s first malt whisky distillery, Shinjiro had an unprecedented opportunity: he could establish the process, institute the quality, and extract the flavor expressions that ultimately determined how Japanese whisky would be perceived. (Following his example, Suntory continues to prioritize equipment over offices, wits ahead of authority, and reality before appearances.) But first, Shinjiro had to overcome failure—again.

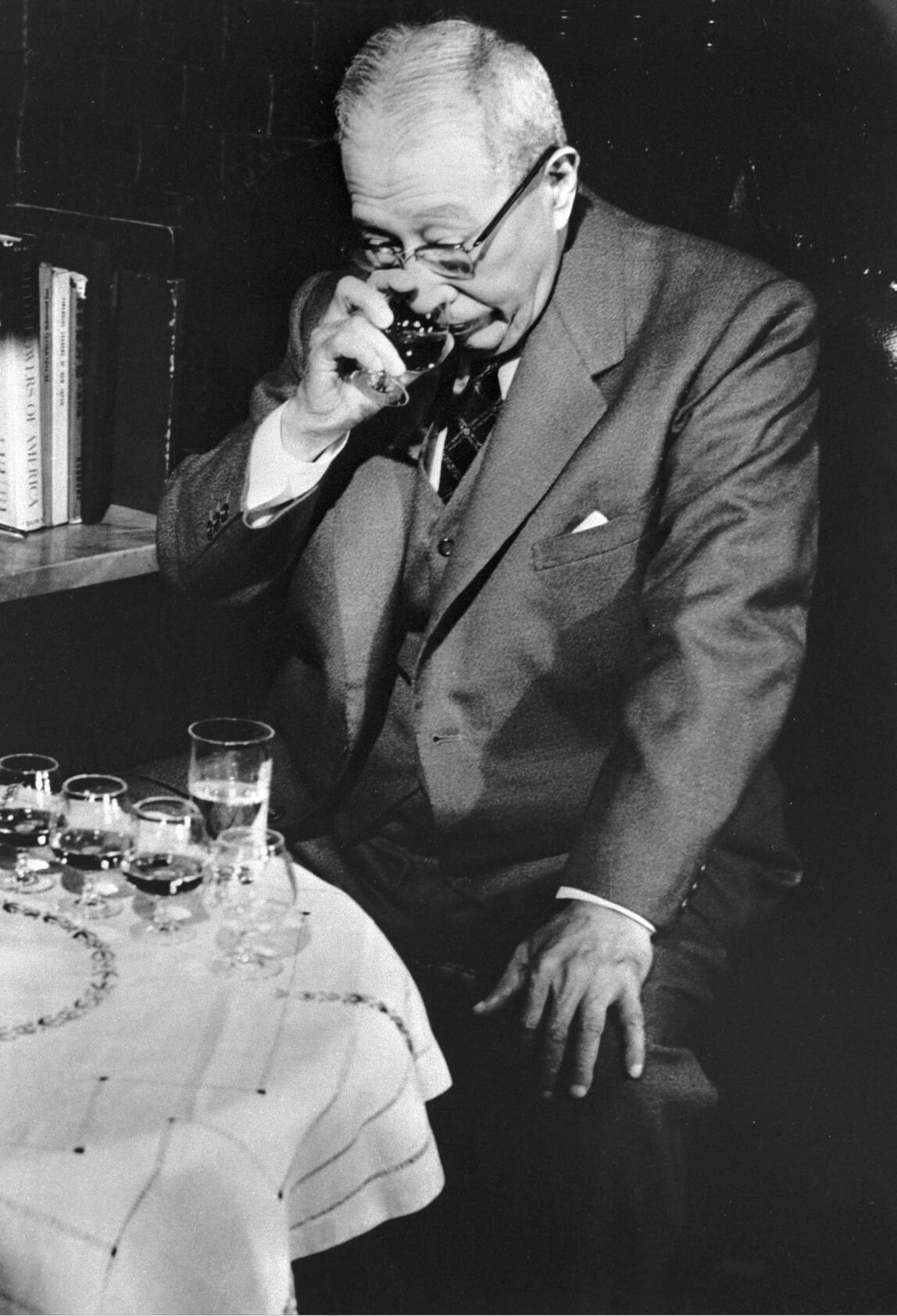

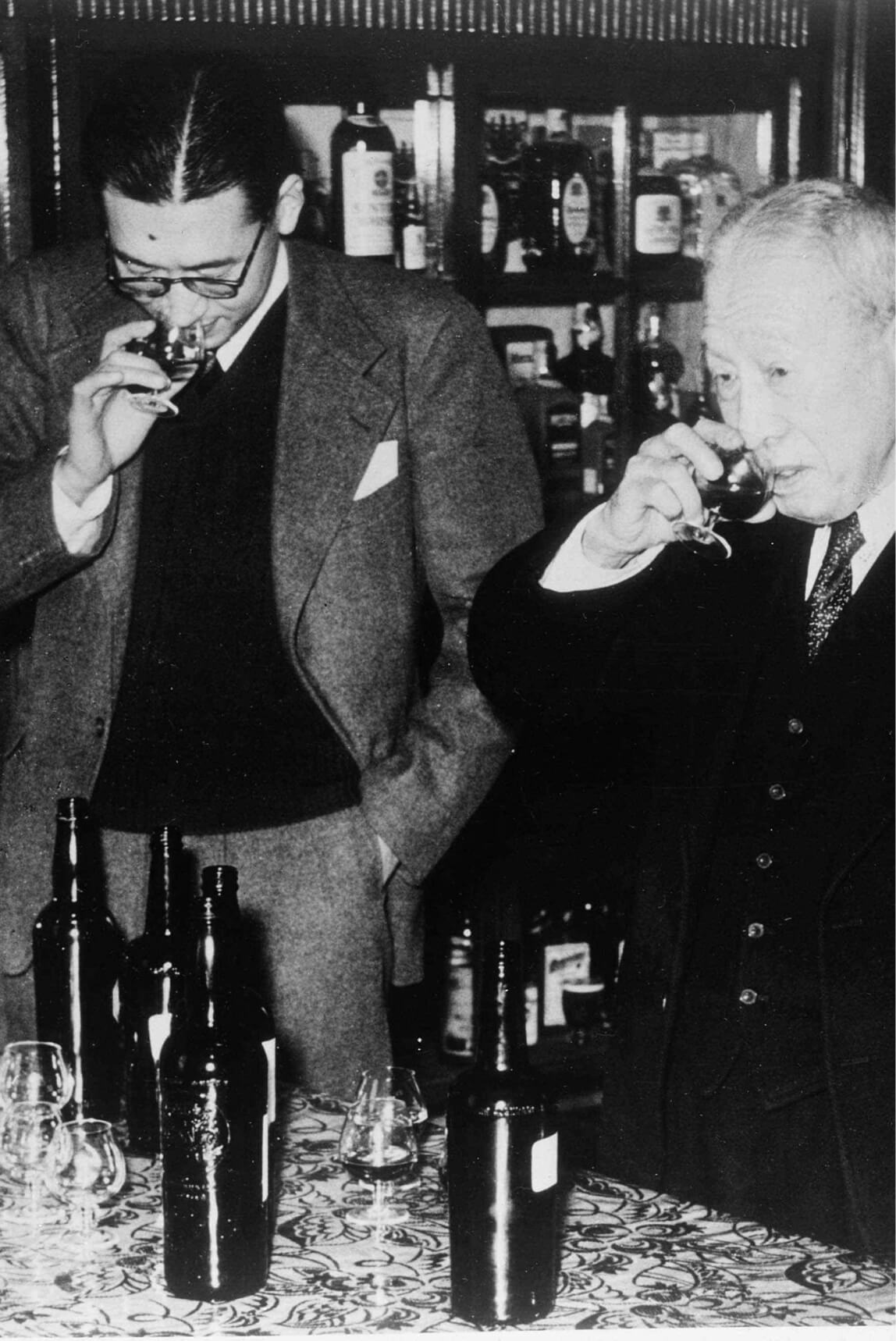

As with his initial foray into the wine business, his original product, Shirofuda (White Label), failed. Consumers found the blend (called Suntory Whisky) harsh and too smoky. So Shinjiro went back to work. His devotion to monozukuri, or the relentless pursuit of perfection through true craftsmanship, would not only rescue his investment in Yamazaki but imbue the company with its renowned commitment to artisanal skill for decades to come. Relying on his own nose and palate, Shinjiro obsessively tested new processes and new blends. He’d often wake up in the middle of the night with a fresh idea and jot it down under the glow of the flashlight he kept near his pillow. Sometimes, he’d sleep at the distillery.

In 1937, 14 years after founding Yamazaki, Shinjiro tasted success at last with the launch of his original blend. Unlike Shirofuda, which mimicked Scotch whisky, Shinjiro ensured that every detail of this new blend—from its production to its name to its bottle—was crafted with “the riches of Japanese nature and craftsmanship.” He again marketed the blend as Suntory Whisky, but the Japanese people lovingly nicknamed it “Kakubin,” after the signature square shape (kaku) of its bottle (bin). Kakubin marked the Suntory family’s quest to honor the natural world while constantly seeking to extract richer, more complex characteristics in their processes.

“IF I GO BACK TO SQUARE ONE FOR HELPING THE NEEDY, THEN THAT’S FINE WITH ME.”SHINJIRO TORII

“Our craftsmanship is there to enhance the blessings of nature,” Nobu says, describing the Yamazaki Distillery as a “very, very sacred place.” As he sees it, the founder’s greatest gift was his ability to unlock the latent flavors of the natural world—to amplify the tastes in the water and grain and forest. Suntory often describes this process as being rooted in bimi, which roughly translates to “good flavor” but conveys something more profound: “It’s about creating taste, pure taste—the sensorial taste of how taste is made,” Nobu says. “The smell, the texture...how you get to the taste of the ingredients.”

As Shinjiro’s success in whisky making grew, so did his passion for philanthropy. Even in his earliest days as a craftsman, he was known to be generous in sharing whatever profits he could afford, often going against financial advisors. In 1921, nearly two decades before “Kakubin” hit the market, Shinjiro established Hojukai, a philanthropic organization whose investments spanned child care, elderly care, tuition assistance, and food scarcity. Even when Suntory fell on hard times, Shinjiro maintained his practice of giving back to society, saying, “I built this company from nothing. If I go back to square one for helping the needy, then that’s fine with me.”

Saji

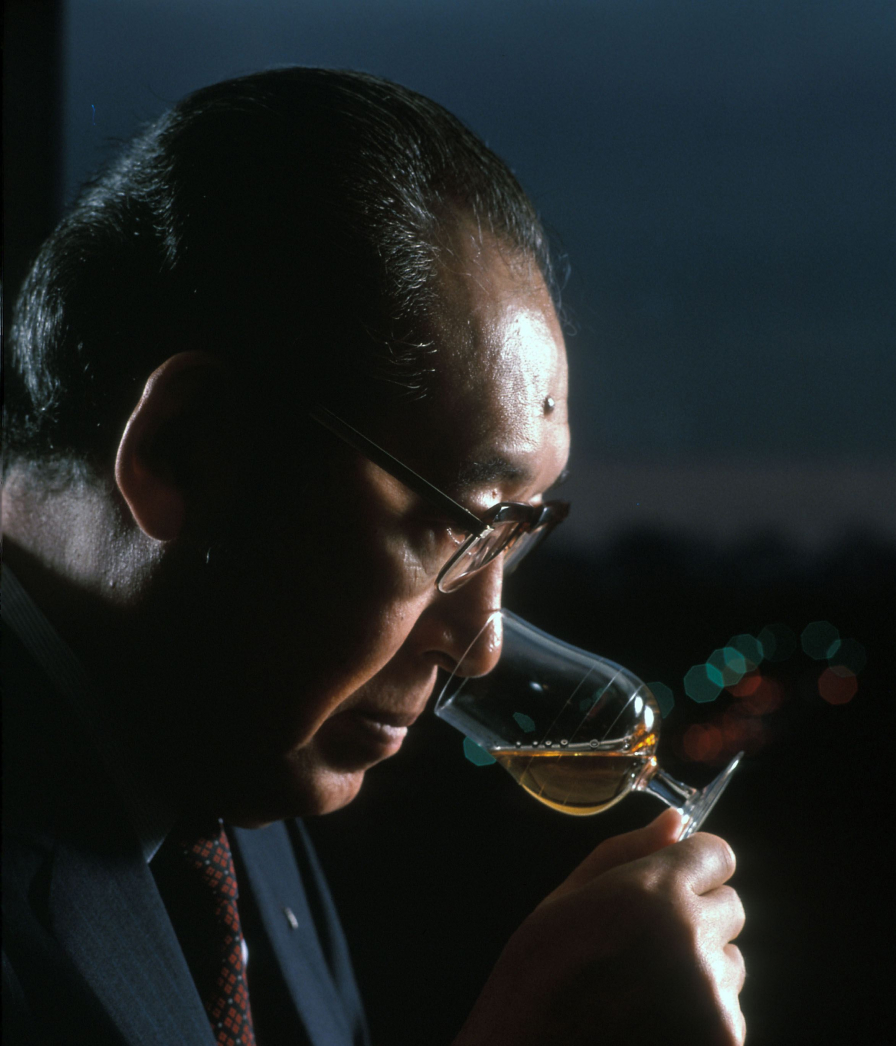

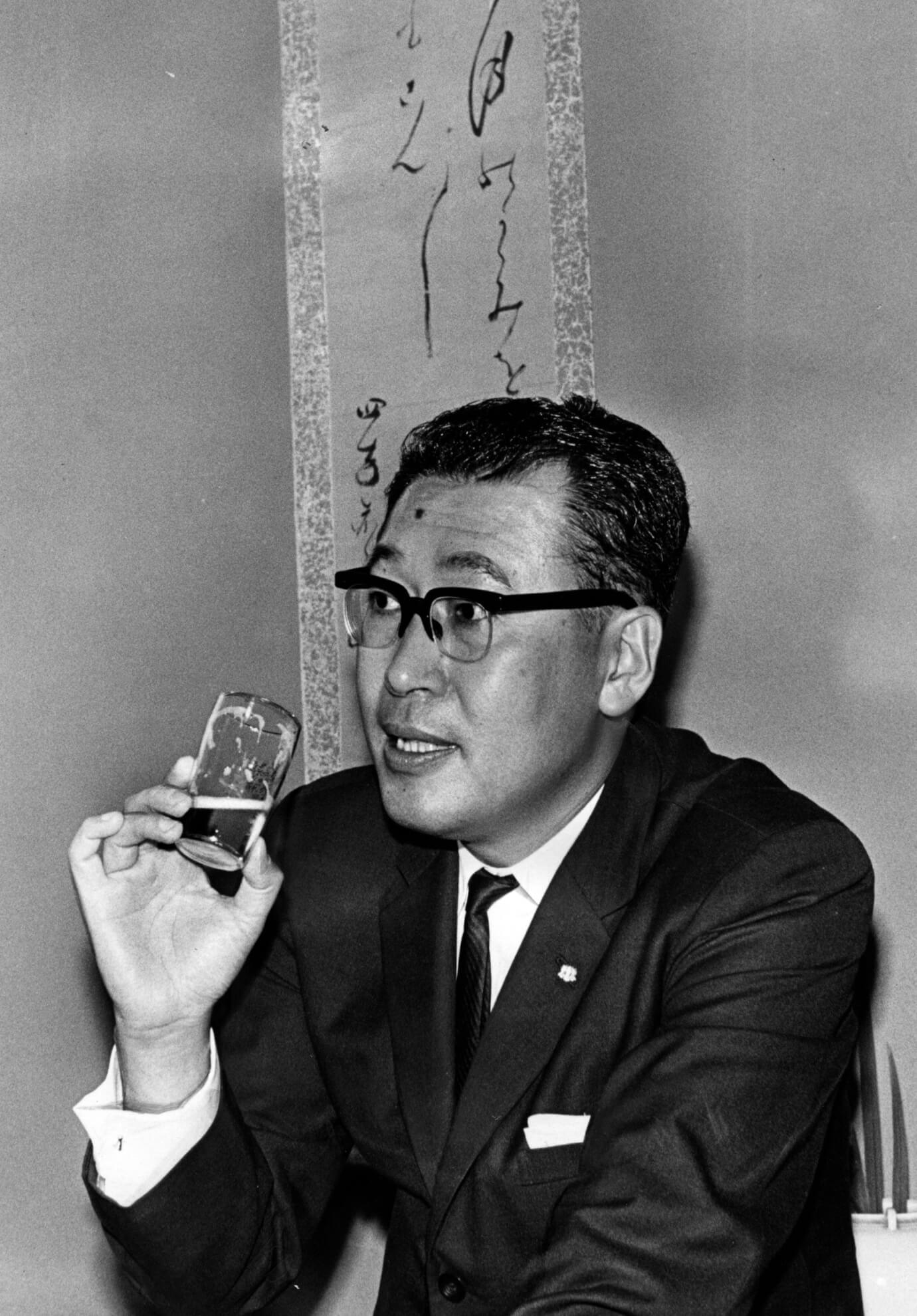

As every pioneer knows, the journey is never finished. When Shinjiro passed the torch to his son Keizo Saji in 1961, Suntory found itself in the hands of a scientist—a graduate of Osaka University’s chemistry program. “Keizo was more scientific,” Nobu says, “while Shinjiro was, in a sense, quite spiritual. They were both visionaries though. Visionaries with big dreams who knew to never give up.”

While Shinjiro pioneered Japanese whisky, Keizo elevated and nurtured Japanese whisky as a culture. Understanding that the Japanese did not favor strong alcohol on its own, Keizo introduced pairing Japanese whisky with local cuisine, revolutionizing the way people could enjoy whisky as a complement to dining—whether that was drinking it neat, cutting it with water (Mizuwari), or mixing it with soda (the Highball). Beyond the product, Keizo created and expanded “cultural experiences” that brought people together. To Keizo, Japanese whisky is only authentic when it is connected to Japanese culture and rooted in experience.

Under Keizo’s leadership, Suntory continued to challenge itself, establishing the inventive-grain Chita Distillery in 1972 and the forested Hakushu Distillery in 1973. The quality of diversity and increased capacity gave Keizo more leeway to innovate as Suntory’s second-generation Master Blender. He broke new ground with Yamazaki’s first pure malt whisky in 1984, introduced Hibiki in 1989, and released the herbal and gently smoky Hakushu single malt whisky in 1994.

“DON’T EVER STOP BELIEVING. DON’T EVER GIVE UP. DON’T EVER FEAR FAILURE.”KEIZO SAJI

Beyond his contributions to Suntory Whisky, Keizo pioneered Suntory’s beer business. Back in the 1950s, when the Japanese beer market was monopolized by the country’s “big three” beer producers, Keizo dreamt of making an original Japanese beer, similar to how his father, Shinjiro, wanted to create an original Japanese whisky. When Keizo passionately consulted his father, it is said that Shinjiro replied, “Yatte Minahare” (pronounced ya-tey mee-na-har-ray), meaning “Don’t ever stop believing. Don’t ever give up. Don’t ever fear failure, and keep pushing forward to create new value.” Today, this value endures at Suntory, calling on every employee to embrace challenges—and potential failure.

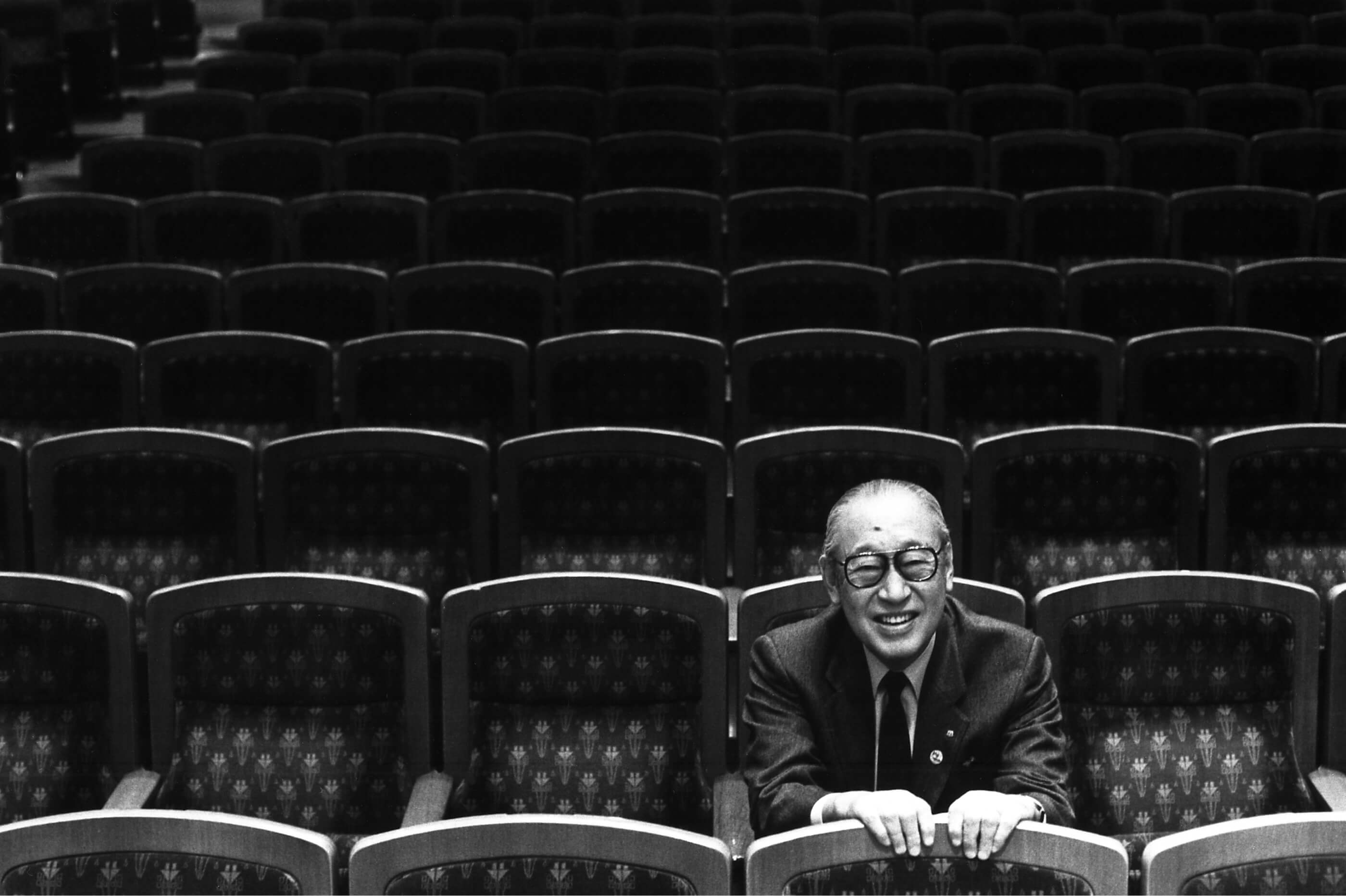

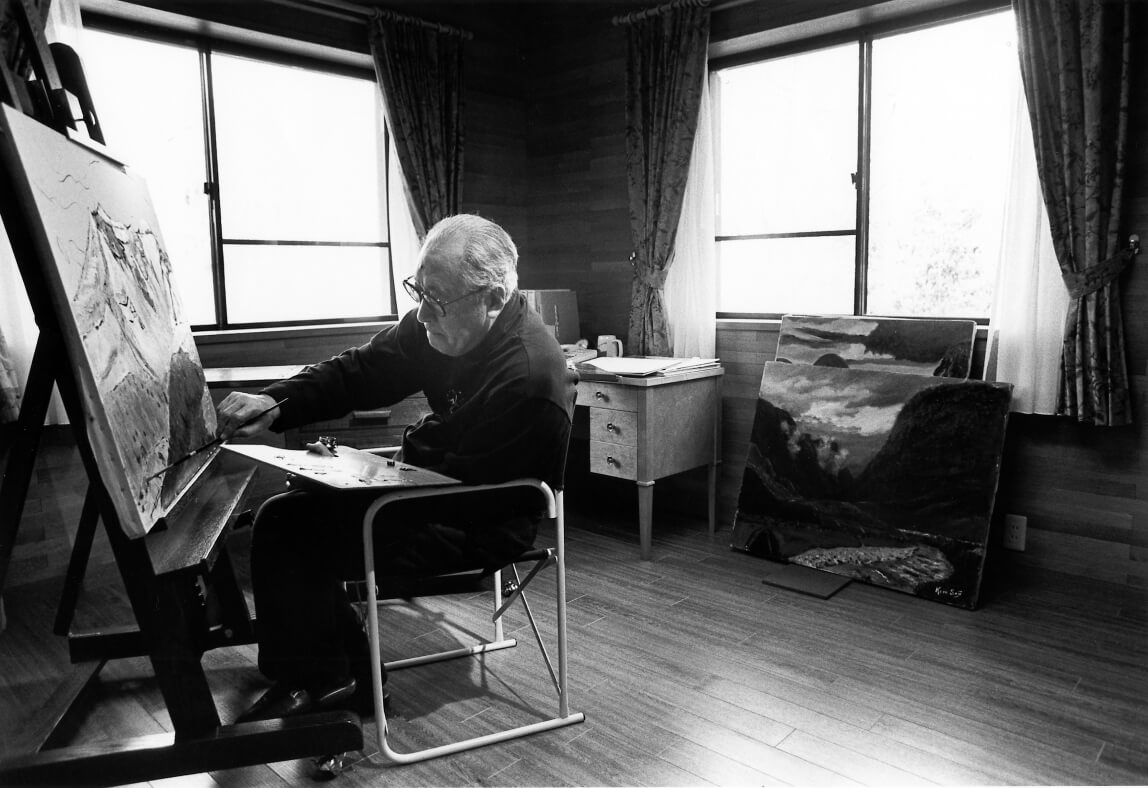

A Renaissance man, renowned Haiku poet, photographer, and patron of the arts, Keizo intuitively recognized that whisky belonged to a larger cultural milieu—one that celebrated the “brilliance of human life” and extended Shinjiro’s commitment to giving back. In 1961, he helped launch the Suntory Museum of Art, which now holds some 3,000 pieces of art, from Japanese antiques to glass arts from around the world, and welcomes 300,000 people annually. He also oversaw construction of Tokyo’s prestigious Suntory Hall, which opened in 1986 and features a vineyard-style, 2,006-seat auditorium. As a space designed for intimate and reverberant aural experiences, Suntory Hall has hosted some of the world’s most renowned classical musicians. Keizo also established the Suntory Foundation for the Arts, which supports young Japanese artists. He was also proactive in advocating for harmony between nature and people. With an underlying belief in the interconnectedness between the wellbeing of animal populations and the future of humankind, he launched the “Save the Birds” initiative and built a bird sanctuary in Hakushu in 1973 to support biodiversity. Such initiatives represented Keizo’s aspiration to build a society where people and nature coexist, which Suntory still upholds today.

These philanthropic endeavors build on the founder’s value of “Giving Back to Society.” The value calls on Suntory to share profits three ways and promote social excellence as a deep-rooted company value. Keizo expanded on that philosophy, insisting that the company should strive to focus on “qualitative prosperity,” or thinking beyond production-oriented goals and contributing to the intangible values that “add colors and flavors to life.” It is a foundational principle behind Suntory’s measured expansion into nonalcoholic, health, and wellness products, as well as its trailblazing history of sustainability investments. Beyond business, it ties into another concept Keizo inherited from Shinjiro: the philosophy of Shin-zen-bi. Shin-zen-bi can be understood as the timeless pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty.

Torii

Master Blender

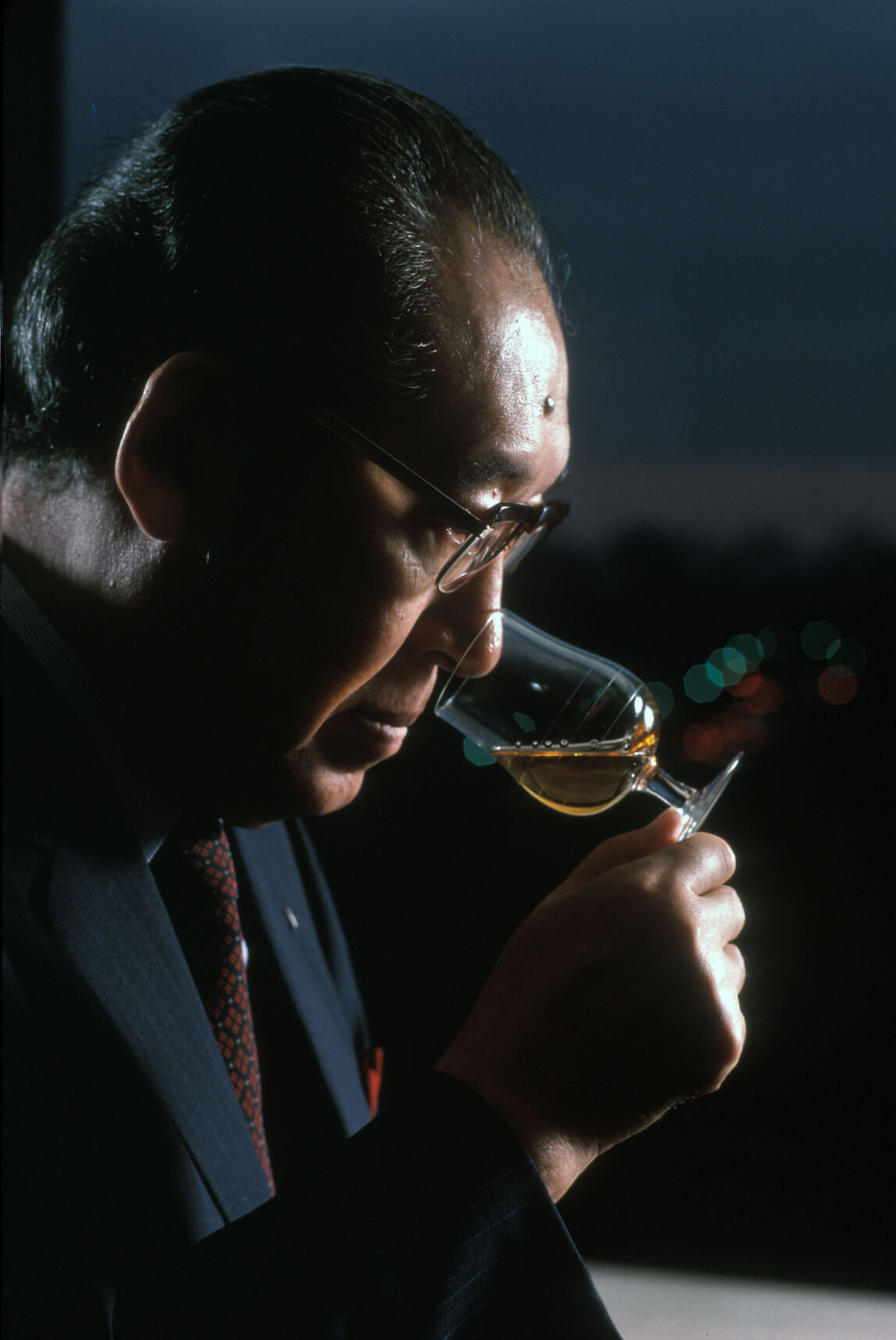

Shingo Torii is known among spirits connoisseurs as the man who helped elevate Suntory on the global stage. When Nobutada Saji (the son of Keizo) became Suntory’s CEO in 2001, he tasked Shingo with elevating Suntory Whisky around the world as the third-generation Master Blender. Shingo is known to be seldom satisfied: a purist at heart, he’s relentless about getting things right and tirelessly commits himself to consistently improve the qualities of Suntory Whisky. He remains inspired by his grandfather’s dream that one day Suntory Whisky would be globally recognized.

Shingo plays a critical role in ensuring the integrity of Suntory Whisky. Back in 1987, whisky sales struggled. But Shingo, like Keizo and Shinjiro before him, believed in Un-don-kon, the philosophy that there are no shortcuts to success; only perseverance. Instead of cutting costs, Shingo and his colleagues decided to invest in a major renovation of the Yamazaki Distillery to increase the diversity of making, or the number of ways they make whisky, both in the front-end and backend processes. Today, Shingo consistently raises Suntory’s standards of bimi, carrying on his predecessors’ respect for artisanship and infusing it with his own art of blending.

“Shingo is an artist deeply inspired by nature,” Nobu says of his uncle. “He wants to make every effort to benefit from nature. His knowledge is enormous and he’s incredible at tasting, even though he doesn’t actually drink much alcohol.” If that sounds like an impediment to success—a missing entry on a master blender’s resume—it appears to be just the opposite in Shingo’s case. “Because he’s not a big drinker, he’s very sensitive,” Nobu says. “It’s his work in the art of blending, the diversity of making, and the obsession to bimi quality that makes Suntory different from competitors.”

It was Shingo’s undeterred commitment to quality and “no compromise” attitude that gained Suntory Whisky its first global accolades. In 2003, the International Spirits Competition (ISC) awarded Yamazaki 12 Years Old its prestigious gold medal. The annual event draws the attention of major press and whisky connoisseurs alike. Suntory’s win changed not only the history of Japanese whisky but the history of whisky itself. Since then, ISC has named Suntory “Distiller of the Year” four times, making Suntory the most highly awarded House of Japanese whisky—and one of the most awarded distillers in the world.

Everything Shingo does epitomizes his commitment, enduring love, and passion for Suntory and monozukuri. In 2008, Shingo published an internal document of guidelines outlining his perspectives on monozukuri. It specified that the story of monozukuri follows Shin-zen-bi—the acknowledgement that there are no shortcuts—and is always rooted in facts; it advocates for uniqueness through craftsmanship, manufacturing methods, and the passion of the makers. As part of this, there must remain a deep appreciation for land, climate, and the need to evolve for the future. “The story that we want to tell is we very much respect the environment that all of our ingredients come from,” Shingo says. “We rely on nature to craft our award-winning portfolio. The waters of Yamazaki and Hakushu, and their rich natural environments, are important to our proprietary craftsmanship. Without nature, there is no craftsmanship. True craftsmanship is not to add or take away, but to heighten the blessings of nature. This opens boundless possibilities. It is the same for whisky making, beer making, wine making—it is always a work in progress.”

“THE STORY THAT WE WANT TO TELL IS WE VERY MUCH RESPECT THE ENVIRONMENT THAT ALL OF OUR INGREDIENTS COME FROM.”SHINGO TORII

In 2005, the company introduced the phrase Mizu To Ikiru as a way to bring Suntory’s DNA to life. As interpreted by the company in 2023 for global audiences, Mizu To Ikiru means “sustained by nature and water.” It not only crystalizes Suntory’s commitment to protect water resources all over the world, but it communicates Suntory’s purpose: “to inspire the brilliance of life, by creating rich experiences for people, in harmony with nature.”

Looking ahead to Suntory’s second century, Nobu could not be more optimistic. “My dream is to see Suntory Whisky all over the world, to see people enjoying our whiskies in any country that I visit.” Achieving that degree of global reputation is less about business and more about heart, he believes. It requires affirming Suntory’s commitment to its foundational principles every day: A respect for nature. A commitment to craft. A love for the people. And an embrace of Yatte Minahare.

“We have to keep challenging. We have to keep pushing the boundaries,” Nobu says. “That’s what pioneers do.”

Since Shinjiro Torii founded the company in 1899, three generations of Toriis have served as Master Blenders — each with an unwavering commitment to monozukuri and elevating Japanese whisky around the world.